by Monika Ingeborg Maeckle

With eight years of school, a stubborn streak backed by a monumental work ethic and a hefty dose of optimism, Hilde Maeckle exhibited a profound selflessness in building a life and family in the U.S. after World War II left Germany in ashes. She became a beloved mother of two and “Oma” to five grandchildren and eight great grandchildren.

Born to Emma Basler and Cornelius Pfeffer on November 27, 1932, she was the middle sister to Ingeborg and Gertrude and was almost seven years old when World War II began.

Her father left for the front in 1939, leaving Emma a single mom working as a housekeeper for the local army base in Stuttgart. Hilde and her sisters sometimes tagged along. According to Hilde, the outings were fun for the girls.

When the air raids became frequent, Hilde spent much of her childhood in bomb shelters and separated from her family–first in the German regional capital of Stuttgart, and later in the countryside.

“When the sirens wailed during the night, we got up, grabbed our blankets and headed for the cellar where each renter had a stall to store root vegetables and canned goods. There, mother had fixed some cots where we could lie down,” Hilde recalled.

Trapped in the basement under the old city wall, Hilde became so nervous she started sleepwalking. Her mother had to corral her so she didn’t leave the four-story walk-up apartment where they lived.

“They always told us kids: as long as you can hear the whistle, it’s not going to hit us,” Hilde recalled. Eventually, their apartment house was bombed, their top floor apartment incinerated, except for one room.

When the German government decided school age children would be removed from big city targets and placed with farm families in the countryside for safety reasons, my mother’s education halted. She had always loved school and reading, although she was never allowed to read during the day until all chores were done. Night reading was out, she remembered, because electricity cost too much.

Oma’s older sister Inge went to live with a family in Freudenstadt while she was sent to a village called Langenau. “I still see myself on that train, all these crying kids, myself included, who did not want to leave their mothers,” Hilde recalled.

These traumatic episodes defined my mother’s life. As an adult, she was known for hoarding groceries and an almost obsessive need for order that served her well in her profession as a bookkeeper. She also embraced a persistent sweetness and optimism. “This, too, shall pass” and “It’ll get better”–catchphrases she often repeated to her own children during tough times, were words her mother always recited in the bomb shelter.

After the war, my mother returned home, which was now Ulm-on-the- Danube, to find she had a brother, Dieter, who was conceived during a furlough visit. Her father, Cornelius, had been captured by the Americans and sent to California, thus Emma had to single handedly feed four children. It wasn’t easy, and she and her sisters often had to beg for food, a humiliation that explains her frugal nature in adulthood. Their most common meal: fried potatoes with skim milk.

With the help of her mother’s brother, Erwin Basler, the family set up a household in Arnegg, outside Ulm, which was “in the country” and on the banks of the Blau River. That’s where, at the age of 17 in 1949, she met my father.

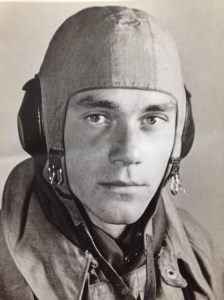

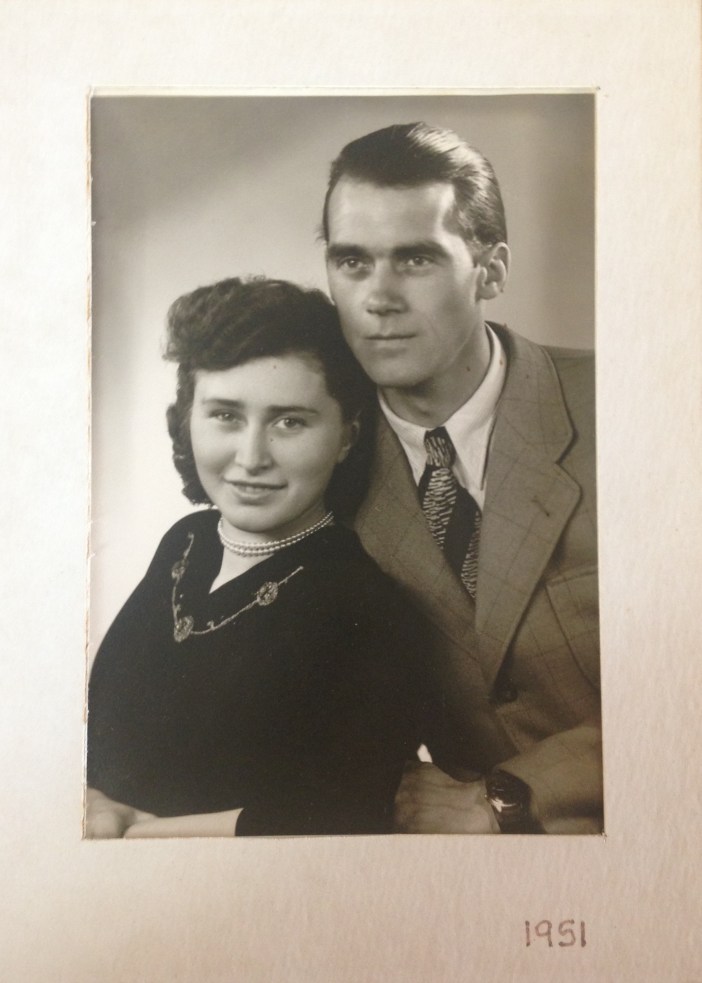

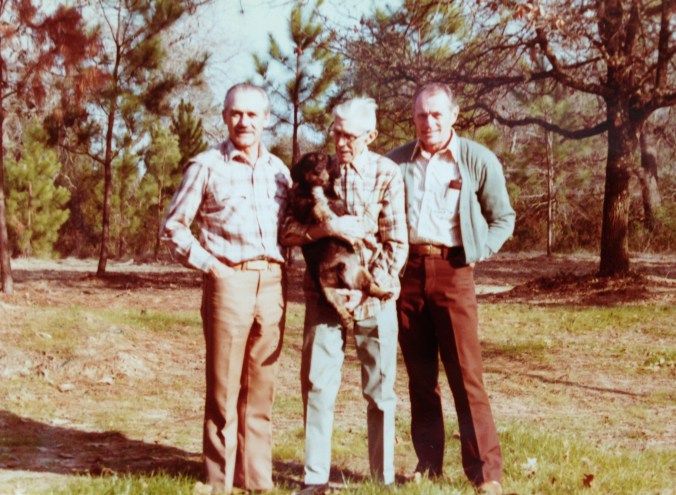

It was a classic swimming outing with her friend Brunhilde, but the dapper, motorcycle-riding John, who had just returned from four years as a prisoner of war in England, and his cousin Albert Lang, “made themselves at home on our blanket and would not move,” she remembered. The young men–my father was 28–invited the girls to a party at Albert’s cabin in the forest and after almost two years of dating, on July 19, 1951, Hildegard Pfeffer, 18, married Johannes “Hanne” Maeckle, 29.

Hilde commuted to Ulm on a bicycle my father built for her and worked as a bookkeeper, while John hustled work as a cabinet maker. It was tough going. In 1952, cousin Albert immigrated to the United States and wrote effusive letters home to his cousin John, about the massive building opportunities in Texas. Soon my parents were planning their move to the United States

My parents sold all their belongings in November 1953, and boarded a freighter destined for Tampa, Florida. My mother was the only woman among 49 men on board. My brother Mike was conceived on that ship, and I arrived two years later.

Albert picked my parents up in Tampa and drove them to Texas where the cousins started a building business in the booming Dallas suburb of Richardson. My mother served as bookkeeper for the company.

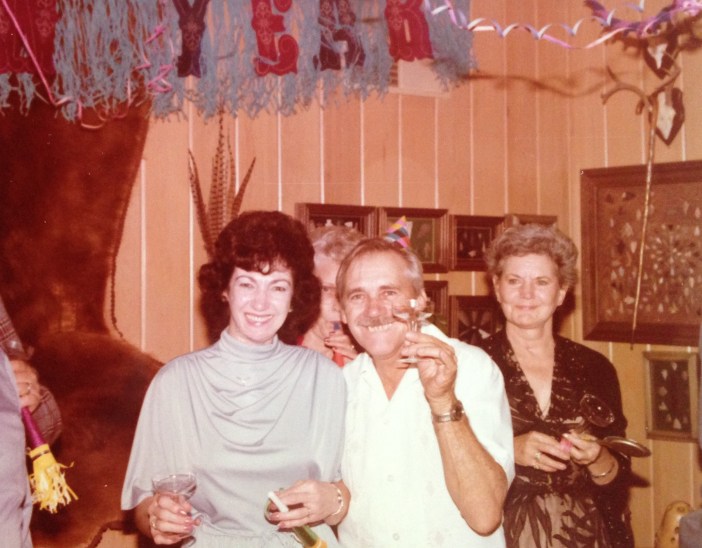

Fitting in with the Dallas suburbs in post-war America for a young female German was no easy task, but my mom found her tribe in a bowling league. She joined a women’s team that went to the championships in 1966. She also shared her love of dancing, cooking and parties with her U.S. friends. Polka parties, with her meticulous cheese-and-salami platters, were a fixture of my upbringing.

“Oma” as she came to be known in her later years also loved to play the accordion, cook, sew, and travel. Her Spätzle (a German pasta) and Pfannekuchen (crepes) are cherished in the family and with friends and neighbors fortunate enough to have sampled them. She passed along these cooking traditions with gusto and pride.

My mom taught me the skills of domesticity–cooking, sewing, and supporting family. She also believed in relishing life, through travel, adventures and celebration, making the most of every birthday and holiday. She was always there for me and my brother, and any friend or loved one in need of help or support, a quiet pillar of unconditional love.

She loved animals as much as her own children and grandchildren–especially her 26-year-old parrot, Bismarck, who ate every meal with my parents until the bird passed in 2013. Her affection for dogs and cats only seemed to grow as dementia took hold, and we always took our dog Cacteye to visit her at the Forum senior care facility where she spent the final months of her life.

In classic waste-not-want-not fashion, Oma asked that her body be donated to science, and it now being utilized by the University of Texas Health Science Center for students of nursing, dentistry and medicine.

She loved well and was well loved. In her oral history, her final advice for those who follow: “Before anyone settles down they should fly, fly, fly.”

We miss you, beloved Oma. You live in our hearts–forever loved, always missed, never forgotten.

Do you have a great memory or photo of Hilde “Oma” Maeckle? Please share in the comments below.

Hilde Maeckle is survived by her daughter Monika Maeckle, son-in-law Robert Rivard and grandsons Nicolas and Alexander Rivard of San Antonio; her son, John Michael Maeckle and daughter-in-law Vicki Yantis Maeckle of Kalispell, Montana; granddaughter Melinda Maeckle Martin, son-in-law Robert Martin, great grandchildren Amara and Aleric Martin of Spokane, Washington; grandson Christopher Maeckle and great grandson Jacob Freimuth of Spokane; and grandson Daniel Maeckle and grandchildren Olivia, Donovan and Nivaeh Maeckle of Spokane.

Family and friends will celebrate Hilde Maeckle’s life at a future time to be determined. A Hildegarden has been established and will be maintained at The Forum at Lincoln Heights in San Antonio where she spent her final months. In lieu of flowers, donations to the Monika Maeckle and Robert Rivard Endowment at UTSA, a scholarship fund earmarked for first generation Americans, the San Antonio Food Bank or Humane Society of San Antonio would be welcomed.

Read John Maeckle’s life story here.